What Robin Wall Kimmerer's "The Serviceberry" Teaches Us About Supporting Authors

How Robin Wall Kimmerer's The Serviceberry affected me

As I sit at my computer, looking at the author websites I've designed, I can't stop thinking about the stories behind each one. There's the fantasy novelist who worried her work wasn't "commercial enough," the romance author who felt guilty charging readers for her heartfelt stories, and the picture book writer who questioned whether her voice mattered in an oversaturated market.

Each of these brilliant creators carried the weight of an industry that too often treats authors as commodities to be mined rather than artists to be nurtured.

This reflection became even more poignant after reading Robin Wall Kimmerer's latest work, The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. In this profound exploration of gift economy versus market economy, Kimmerer offers a vision that could revolutionize how we think about supporting authors and the creative community at large.

Introduction to The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

Robin Wall Kimmerer, the botanist and Indigenous scholar who captured hearts worldwide with Braiding Sweetgrass, returns with The Serviceberry, a meditation on abundance that challenges our fundamental assumptions about scarcity and value.

Published in 2024, this book uses the humble serviceberry tree as a lens through which to examine two radically different economic systems: the market economy that dominates our world, and the gift economy that has sustained Indigenous communities for millennia.

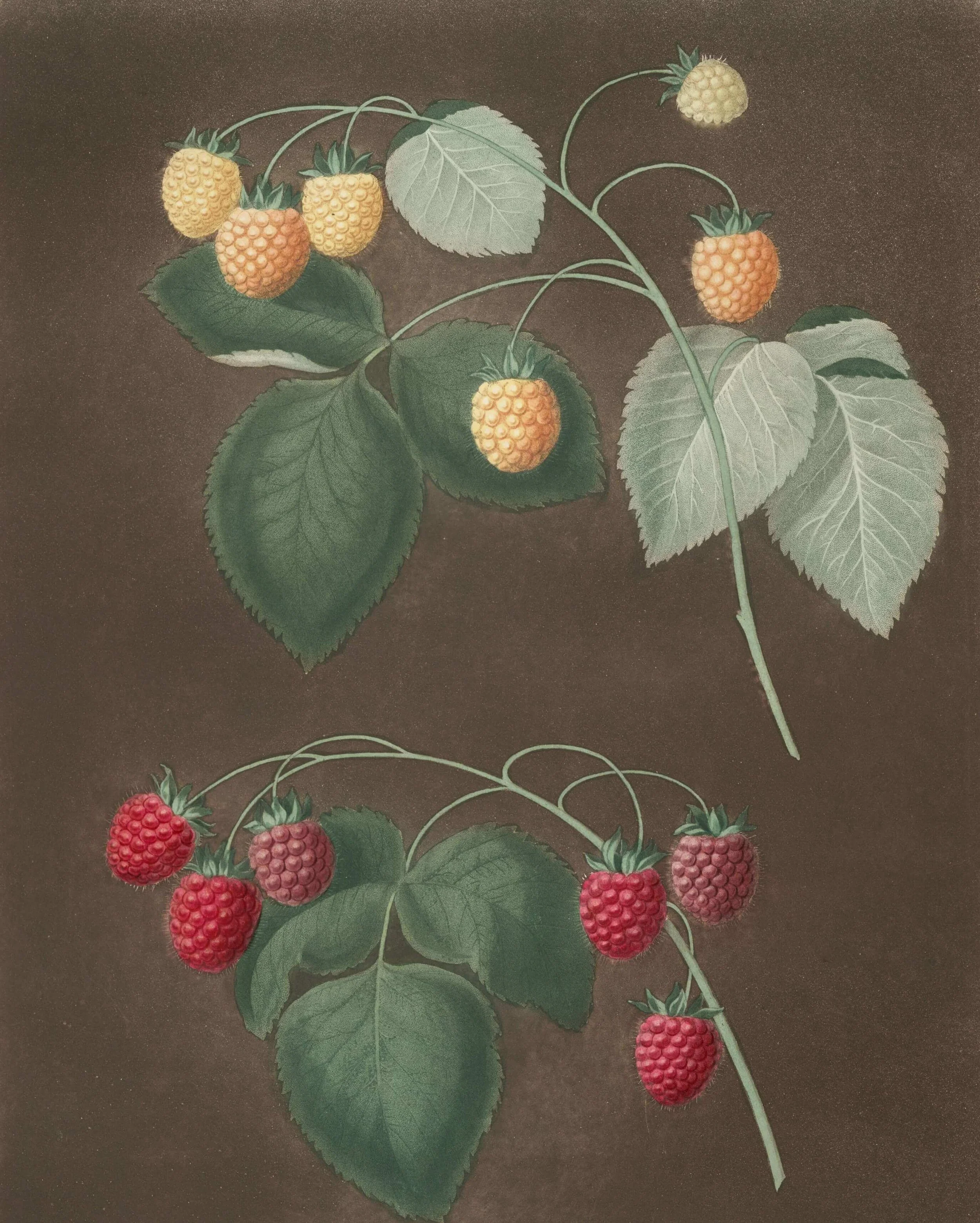

The serviceberry, Kimmerer explains, produces abundant fruit that feeds not just humans, but bears, birds, and countless other creatures. The tree doesn't hoard its berries or charge rent for access to its branches. Instead, it gives freely, trusting in the reciprocal relationships that have sustained forest ecosystems for thousands of years. When animals eat the berries, they spread the seeds, ensuring the serviceberry's continuation.

This isn't charity—it's a sophisticated economic system based on mutual benefit and long-term thinking.

Kimmerer, drawing on her expertise as a Western-trained scientist and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, bridges Indigenous wisdom with contemporary environmental science. Her central thesis is both simple and revolutionary:

What if we organized our economic systems around abundance and reciprocity rather than scarcity and extraction? What if we measured success not by how much we accumulate, but by how much we give away?

This question becomes particularly relevant when we consider the creative economy, where artists and writers are often caught in a system that seems designed to extract their creativity while offering frustratingly little in return.

The parallels between Kimmerer's serviceberry and the author community are striking—and they point toward a more sustainable and fulfilling way of supporting creative work.

The Market Economy's Treatment of Authors as Commodities

The publishing industry, like many creative fields, has increasingly embraced a market economy model that treats authors as resources to be mined rather than artists to be cultivated.

This extraction model is evident in countless ways, from the relentless pressure for content creation to the reduction of complex creative works to simple metrics.

The Extraction Model in Action

In my work with authors, I've witnessed firsthand how the market economy manifests in the publishing world. Authors are expected to be not just writers, but also marketing managers, social media influencers, and content creators. They're told to build their platform before they've even finished their first book, to post daily on multiple social media channels, and to always be on brand.

This constant demand for productivity mirrors what Kimmerer describes as the market economy's fundamental flaw: it treats resources as infinite and relationships as transactional.

Authors are expected to produce content at an unsustainable pace, often burning out before they've had a chance to develop their craft or find their authentic voice.

The result? A landscape littered with exhausted writers who've been mined until they're empty, their creativity extracted like fossil fuels from the earth.

I've seen authors who haven't written a word in months because they're too busy creating Instagram reels about their writing process.

I've worked with talented storytellers who've abandoned their passion projects to chase trending topics, hoping to catch the algorithm's attention.

The irony is absolutely heartbreaking: in trying to succeed in a system designed around scarcity thinking, these authors often deplete the very creativity that made them want to write in the first place.

Scarcity Mindset in Publishing

The market economy's scarcity mindset is perhaps most evident in how the publishing industry positions authors against each other. There's an assumption that shelf space is limited, that readers can only love one book at a time, and that success must come at the expense of other writers.

This creates a competitive environment where authors feel they must fight for every reader, every review, every moment of attention.

This scarcity thinking extends to how we value creative work. Books are often treated as disposable content, consumed quickly and forgotten. Authors are pressured to write faster, publish more frequently, and constantly reinvent themselves to stay relevant. The focus on quarterly sales figures and immediate market response leaves little room for the slow, contemplative work that often produces the most meaningful art.

The "winner-take-all" mentality means that only bestsellers are considered truly successful, while the vast majority of authors—those who build smaller but devoted readerships, who write for niche audiences, or who create work that takes time to find its audience—are often dismissed as failures. This binary thinking ignores the rich ecosystem of storytelling that exists beyond the bestseller lists.

The Commodification Problem

Perhaps most damaging is how the market economy reduces authors to their sales numbers and platform metrics.

I've worked with incredibly talented writers who've been told by industry professionals that their work is "good but not marketable," as if creativity were a commodity to be evaluated solely on its immediate commercial potential.

This commodification creates a feedback loop where authors begin to see themselves as products to be optimized rather than artists to be nurtured.

They start writing to market trends rather than exploring their authentic voice, creating content designed to go viral rather than stories that need to be told.

The result is often work that feels hollow and manufactured—the creative equivalent of industrial agriculture's monocrops.

The exhaustion that comes from this approach is real and devastating.

Authors who once loved writing begin to dread opening their laptops. The joy of storytelling is replaced by the anxiety of performance metrics. Creativity, which should be a renewable resource, becomes depleted through overuse and under-nourishment.

Envisioning a Gift Economy for Authors

But what if there were another way? What if, like Kimmerer's serviceberry, the author community could operate on principles of abundance rather than scarcity? What if we could create systems that nurture creativity rather than extracting it?

Abundance vs. Scarcity Thinking

The first step in imagining a gift economy for authors is recognizing that stories, like serviceberries, can be abundant.

There's no shortage of readers in the world—there's a shortage of connection between readers and the books they'd love.

There's no limit to the number of authors who can succeed simultaneously—there's a limit to how many voices we're willing to amplify.

In my work designing websites for authors, I've seen how abundance thinking can transform a writer's relationship with their craft.

When authors stop seeing other writers as competition and start seeing them as collaborators in the great project of storytelling, everything changes.

We become more generous with their praise, more willing to share opportunities, more open to supporting each other's work.

This shift in perspective has practical implications. Instead of hoarding writing tips or marketing strategies, authors in an abundance mindset share freely, knowing that lifting others up doesn't diminish their own success. They celebrate other writers' achievements, understanding that a thriving literary community benefits everyone.

The abundance mindset also recognizes that readers have an enormous capacity for books. The same person who loves one fantasy novel isn't limited to loving only that one—they're likely to seek out more books in the genre, creating opportunities for multiple authors.

When we stop treating readers as a finite resource to be captured and start seeing them as community members to be served, we open up possibilities for connection and growth.

Reciprocity in the Author Community

Kimmerer writes that in a gift economy, "the currency is relationship."

This principle, applied to the author community, suggests that the most valuable thing writers can offer each other isn't money or platform sharing, but genuine relationships and mutual support.

I've witnessed this reciprocity in the author communities I’m blessed to be a part of. When writers operate from a gift economy mindset, they naturally support each other in ways that go beyond simple quid pro quo arrangements. They share opportunities without expecting immediate returns, mentor newer writers without calculating the time investment, and celebrate each other's successes without keeping score.

This reciprocity creates a web of relationships that strengthens the entire community.

Authors who support each other's work find that their own work is supported in return—not as a transaction, but as a natural consequence of building genuine relationships.

The writer who enthusiastically promotes another author's book often finds that their own work receives similar support, not because they asked for it, but because they've contributed to a culture of generosity.

Cross-pollination of ideas becomes natural in this environment. Authors collaborate on projects, share resources, and inspire each other's work.

The result is a richer, more diverse literary landscape where different voices amplify each other rather than competing for dominance.

Redefining Success and Value

Perhaps most importantly, a gift economy for authors would require redefining what success looks like. Instead of measuring value solely through sales figures and platform metrics, we could recognize the many ways authors contribute to their communities and culture.

Some authors are master teachers, nurturing the next generation of writers through workshops and mentorship. Others are community builders, creating spaces where readers and writers can connect. Still others are cultural preservers, telling stories that might otherwise be lost.

These contributions have immense value, even if they don't translate directly to bestseller status.

A gift economy would also recognize the long-term value of creative work. Some books find their audience immediately, while others take years or decades to be fully appreciated. Some authors produce work that changes individual lives in profound ways, even if it doesn't achieve massive commercial success.

These contributions deserve recognition and support, not dismissal as "commercial failures."

Practical Applications: Building Author Abundance

The vision of a gift economy for authors isn't just theoretical—there are practical ways to begin implementing these principles in our creative communities.

For Individual Authors

Authors can begin embracing gift economy principles in their own careers by shifting from competitive to collaborative thinking.

This might mean genuinely promoting other authors' work without expecting anything in return, sharing writing resources and opportunities freely, or offering mentorship to newer writers.

Building authentic relationships with readers becomes more important than growing follower counts. Authors in a gift economy focus on creating meaningful connections with their audience, understanding that a smaller group of engaged readers is more valuable than a large but disengaged following.

This approach also means being selective about opportunities and partnerships, choosing to work with people and organizations that align with gift economy values rather than those that perpetuate extraction models. It means saying no to projects that drain creativity without offering meaningful reciprocity.

For the Publishing Industry

Publishers and literary organizations can support gift economy principles by creating sustainable career paths for authors, investing in long-term author development rather than expecting immediate returns, and recognizing diverse forms of success beyond bestseller status.

This might mean offering authors more supportive contracts that don't require constant productivity or investing in marketing approaches that build genuine reader communities rather than chasing viral moments.

The industry could also work to reduce the adversarial relationship between authors and publishers, moving toward partnership models that recognize the mutual benefit of supporting creative work over the long term.

For Author Communities and Organizations

Writing organizations can foster gift economy principles by creating mutual aid networks. These can be places where authors support each other through challenges, establish skill-sharing initiatives where writers teach each other, and advocate for better industry practices.

These communities can celebrate diverse voices and stories, creating space for authors who might not fit traditional commercial categories but who contribute valuable perspectives to the literary landscape.

They can also work to dismantle the scarcity mindset that pits authors against each other, instead fostering collaboration and mutual support.

The Website Designer's Role in Author Abundance

As someone who works directly with authors to create their online presence, I've had to examine my own role in either perpetuating or disrupting the extraction model. The website design industry often operates on transactional principles—deliver a product, collect payment, move on to the next client.

But what if we could operate from gift economy principles instead?

Moving Beyond Transactional Relationships

In my practice, I focus on building websites that serve authors' long-term growth rather than just their immediate marketing needs.

This means creating educational resources that help authors understand their websites, building relationships that extend beyond the project timeline, and designing with brand sustainability in mind.

Instead of just delivering a pretty website, I try to create lasting value by teaching authors how to maintain and grow their online presence. I share resources freely, connect authors with each other, share my clients’ launch day announcements, and build community through my design work.

This approach has created deeper, more satisfying relationships with my clients; a tiny example of how we each can contribute to a more supportive author community for us all.

Supporting the Author Ecosystem

By creating websites that help authors build genuine connections, I help contribute to an abundance mindset.

By connecting authors with each other and facilitating collaboration, I can strengthen the reciprocal relationships that sustain creative communities.

This means being selective about the projects I take on, working with authors who share these values, and using my platform to promote gift economy thinking in the creative community.

It means seeing my work not just as a business transaction, but as a contribution to the larger project of supporting storytellers and their essential work.

Cultivating Creative Abundance

Kimmerer's serviceberry offers us a powerful metaphor for what the author community could become.

Like the tree that gives freely of its fruit, trusting in the reciprocal relationships that sustain the forest, authors can create abundance by supporting each other, sharing resources, and building genuine community.

This doesn't mean abandoning the practical realities of making a living as a writer.

Authors still need to pay their bills, and sustainable creative careers require financial support. But it does mean examining the systems and mindsets that currently dominate the industry and asking whether they truly serve the people they claim to support.

The gift economy model suggests that by focusing on relationships, reciprocity, and long-term thinking, we can create a more sustainable and fulfilling creative ecosystem.

Authors who support each other's work, share resources freely, and build genuine connections with readers are more likely to thrive over the long term than those who operate from scarcity and competition.

As readers, we can support this shift by recognizing that the books we love come from real people who deserve sustainable careers. We can buy books directly from authors when possible, support independent bookstores, and engage meaningfully with the writers whose work touches our lives.

As industry professionals, we can work to create systems that nurture creativity rather than extracting it, that support authors' long-term development rather than demanding immediate returns, and that recognize the true value of storytelling in our culture.

The serviceberry reminds us that abundance is possible, but it requires a different way of thinking about value, success, and community. For the author community, embracing these principles could mean the difference between a landscape of exhausted, competing individuals and a thriving ecosystem of mutual support and shared success.

In the end, Kimmerer's vision challenges us to imagine what becomes possible when we move from scarcity to abundance, from extraction to reciprocity, from competition to collaboration. For authors and those who support them, this shift could be transformative—creating not just sustainable careers, but a literary culture that truly serves both storytellers and their communities.