When 'Gentle Death' Becomes Genocide

Language has power.

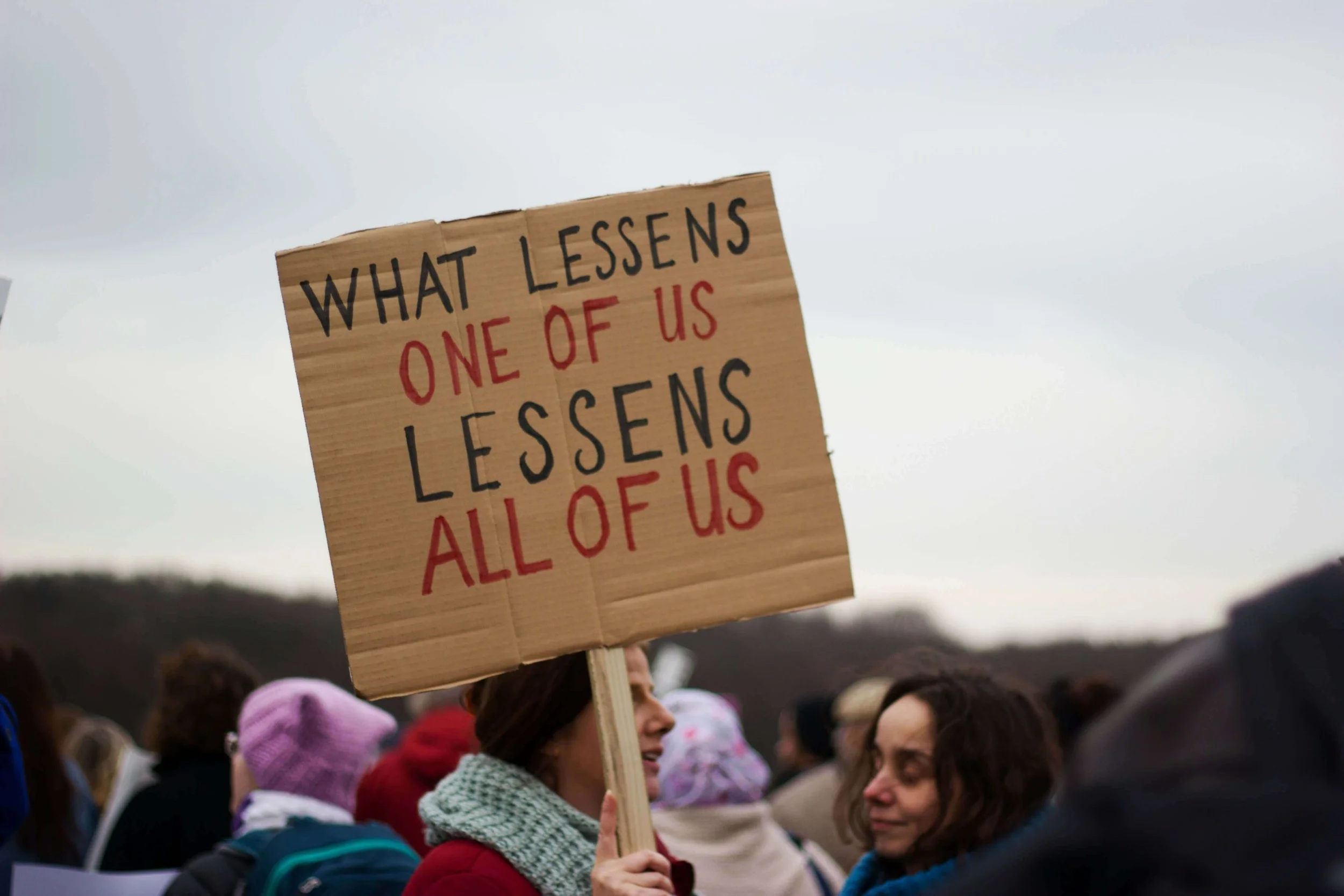

The words we use to describe policies, people, and practices shape how we think about them—and ultimately, how we act.

No one should understand this fact more than authors.

When Nazi officials coined the term "Operation Gentle Death" for their systematic murder of disabled individuals, they weren't just creating propaganda.

They were demonstrating how political language and media manipulation can make the unthinkable seem not only acceptable, but compassionate.

Today, as we witness similar patterns of language manipulation around immigration enforcement, detention policies, and the treatment of vulnerable populations, the lessons from Operation T4 become urgently relevant.

Understanding how "gentle death" became genocide isn't just historical education—it's essential preparation for recognizing propaganda techniques and standing up for human rights in our own time.

This is the final article in a three-part series. Start with article 1, ”The Author's Burden: How Philippe Aziz Documented the Undocumentable," and continue with article 2, "The Power of Professional Resistance," for the complete context.

The Nazi Playbook: How Political Language Paved the Way for Murder

Philippe Aziz's documentation of Operation T4 in “Doctors of Death Volume 4: In the Beginning There Was the Master Race" reveals a chilling pattern: systematic dehumanization always begins with careful word choice and media manipulation.

The Nazis didn't announce plans to murder disabled people. Instead, they spoke of "racial hygiene," "life unworthy of life," and "merciful release from suffering."

"Operation Gentle Death" wasn't accidental phrasing—it was strategic messaging designed to make killing sound compassionate.

Disabled individuals weren't described as people being murdered, but as "burdens" being "relieved of their suffering."

Families weren't told their loved ones were killed, but that they had died of "natural causes" after receiving "medical treatment."

This linguistic manipulation served multiple purposes:

It allowed perpetrators to maintain psychological distance from their actions, describing murder as medicine and cruelty as kindness.

It made public acceptance easier by framing murder as humanitarian intervention.

Most crucially, it created a bureaucratic language that made systematic killing seem routine, clinical, and medically necessary.

The progression of targets followed the progression of language.

What began with "mercy killing" for severely disabled children expanded to include adults with mental illness, then individuals with physical disabilities, veterans unable to work due to PTSD or war wounds, and eventually anyone deemed "unfit" for society. Why?

Because once the language of elimination was normalized, expanding its application became disturbingly simple.

While T4 was eventually shut down due to public resistance, the success of T4's strategy emboldened Nazi leadership to apply similar approaches to other populations:

The gas chambers invented and tested at disability institutions were then used in death camps.

The bureaucratic processes developed for "gentle death" were scaled up for the Holocaust.

The language that made murdering disabled/mentally ill people acceptable was adapted to justify eliminating Jews, Roma, homosexuals, political dissidents, and anyone else who threatened the regime's vision of racial purity.

Perhaps most importantly, this linguistic foundation made resistance more difficult.

When opponents tried to expose what was happening, they faced the challenge of convincing people that "medical treatment" was actually murder, that "mercy" was actually cruelty.

The euphemistic language had done its work so well that many Germans struggled to believe the reality behind the words.

Modern Echoes: Media Manipulation and Immigration Enforcement

The parallels between Nazi propaganda techniques and contemporary immigration discourse are striking and deeply troubling.

Today's policies targeting immigrants and asylum seekers employ similar linguistic strategies to distance the public from the human cost of enforcement actions and normalize what would otherwise be recognized as human rights violations:

"Detention centers" replace "concentration camps," despite housing people indefinitely without trial in conditions that violate international human rights standards.

"Processing facilities" obscure the reality of separating families and holding children in inadequate conditions.

"Deportation operations" sound bureaucratic and routine, masking the trauma of forcibly removing people from communities where they've built lives.

The euphemism "enhanced border security" covers policies that push asylum seekers into dangerous terrain such as fast-flowing rivers and endless deserts, knowing that many will die as a direct result.

"Zero tolerance" sounds firm and principled while describing the deliberate infliction of suffering on vulnerable people as a deterrent strategy.

Perhaps most disturbing is the exportation of detention operations to facilities in El Salvador, creating physical and moral distance from the consequences of these policies. It’s claimed that since they’re not “our” prisons, it’s not the United States’ moral responsibility what happens there, even as we ship humans there to receive inhuman treatment.

But imagine if Nazi Germany had claimed that their death camps in Poland and other countries weren't their responsibility because they weren't on German soil.

Just as T4 began with disabled children deemed "burdens" on society, contemporary enforcement began with undocumented immigrants described as "criminals" and "invaders."

But the language of "public safety" and "national security" justifies increasingly harsh measures against broader populations, just as "racial hygiene" justified expanding Nazi elimination programs.

What begins with "removing criminals" becomes "protecting communities" becomes "preserving our way of life"—each expansion enabled by language that makes the previous step seem insufficient.

The progression reveals the same pattern Aziz documented in Nazi Germany: no one remains safe once dehumanizing language becomes normalized.

Legal status, citizenship, and even birth certificates provide less protection than people imagine when the underlying rhetoric treats entire populations as threats to be eliminated rather than people deserving protection.

The Expanding Target: When No One Is Safe

The history of Operation T4 provides a crucial warning: persecution rarely stops with its initial targets.

What began as "mercy killing" for severely disabled children became systematic murder of anyone the regime deemed undesirable. The progression followed a predictable pattern that contemporary observers would do well to understand.

First came the "easy" targets—disabled children whose elimination could be framed as relieving suffering. Then adults with mental illness, whose lives were described as "burdens" on society. Next, individuals with physical disabilities who required care and resources.

Each expansion used the framework established for the previous group, gradually normalizing the idea that some lives were less valuable than others.

Once the machinery of elimination was operational and public acceptance established, the Nazi regime expanded targets exponentially. Jews, Roma, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, political prisoners, resistance fighters, intellectuals, and clergy—anyone who challenged Nazi ideology or represented "impurity" in their racial hierarchy became eligible for elimination.

The same pattern emerges in contemporary immigration enforcement. What began with targeting "criminal aliens" has expanded to include individuals with traffic violations, people who missed court dates due to lack of proper notice, and asylum seekers following legal processes.

But the expansion continues beyond immigration status.

Legal immigrants face increased scrutiny and denaturalization proceedings. American citizens are detained based on appearance, names, or inability to immediately produce documentation. Sanctuary cities and states find themselves targeted by federal enforcement actions. Lawyers, journalists, and activists working with immigrant communities face investigation and intimidation.

Even more concerning is the expansion beyond immigration enforcement into broader categories of "undesirable" populations.

Protesters are labeled as "domestic terrorists." Journalists are described as "enemies of the people."

Each group becomes eligible for harsh treatment once the language of elimination becomes normalized.

The progression demonstrates why the resistance to Operation T4 documented by Aziz remains relevant: allowing dehumanizing language to take root creates vulnerability for everyone, not just initial targets.

The medical professionals who resisted T4 understood that protecting disabled patients meant protecting the principle that all lives have value—a principle that, once compromised, endangers everyone.

Contemporary resistance movements recognize the same truth.

Immigration advocates understand that defending undocumented immigrants means defending the principle that human dignity doesn't depend on legal status. Civil rights lawyers know that protecting protesters means protecting the principle that dissent isn't treason.

Authors and librarians defending creative freedom understand that protecting controversial books means protecting the principle that uncomfortable truths deserve expression.

The Power of Speaking Out: Finding Courage Through Historical Precedent

The most important lesson from Aziz's documentation of Operation T4 isn't the horror of what happened—it's the proof that resistance can work and that ordinary people can find courage to stand up for human rights.

The medical professionals, families, and religious leaders who opposed the euthanasia program didn't just maintain their integrity; they created enough public pressure to force the Nazi regime to officially shut down the program in August 1941.

Their success provides a blueprint for contemporary resistance to dehumanizing policies.

The T4 resistance worked because it combined multiple strategies: professional resistance from medical workers, family advocacy from affected communities, religious opposition from moral authorities, and public education about what was really happening behind euphemistic language.

Medical professionals warned families, helping them remove loved ones from danger.

Religious leaders spoke from pulpits, educating congregations about the reality behind "gentle death."

Families organized to share information and create networks of mutual protection.

Each group used their particular authority and platform to expose the truth and protect vulnerable people.

The resistance succeeded because it refused to accept political language and propaganda techniques at face value.

Instead of debating whether "mercy killing" was appropriate medical practice, opponents exposed it as “systematic murder.” Instead of accepting bureaucratic explanations for deaths, they investigated and documented the reality. Instead of trusting government assurances about humane treatment, they demanded access and accountability.

Modern resistance movements employ similar strategies with encouraging results:

Immigration advocates use documentation, legal challenges, and public education to expose the reality behind euphemistic enforcement language.

Medical professionals speak out about the health impacts of detention and separation policies.

Religious leaders provide sanctuary and moral voice.

Journalists investigate and report on conditions in detention facilities.

Professional resistance continues to prove effective. When lawyers flood detention centers to provide representation, when doctors document medical neglect, when teachers refuse to report students' immigration status, when authors tell the stories that expose dehumanizing policies—each act of professional resistance makes systematic oppression more difficult to implement efficiently.

The power of coordinated resistance becomes clear when multiple groups work together.

Legal challenges slow implementation of harmful policies. Public education builds opposition. Professional resistance creates practical obstacles. Media coverage maintains visibility.

Each element reinforces the others, creating sustained pressure that can force policy changes.

Perhaps most importantly, the T4 resistance demonstrates that exposing the truth behind euphemistic language can shift public opinion.

When enough people understand that "gentle death" means murder, that "detention centers" mean concentration camps, that "enhanced enforcement" means deliberate cruelty, support for these policies erodes.

Lessons for Authors: The Responsibility to Name Truth

For authors, the lessons from Operation T4 carry special weight.

Writers understand better than most how language shapes reality, how euphemisms can obscure truth, and how storytelling can either humanize or dehumanize populations.

The Nazi manipulation of language to enable genocide represents everything authors should stand against: the perversion of communication to enable rather than prevent harm.

Authors today face their own version of the choice that confronted medical professionals under the Nazi regime: comply with pressure to soften language, avoid uncomfortable topics, and accept euphemistic framing—or use their platform to expose truth and maintain the integrity of language itself.

The parallel responsibilities are clear.

Just as doctors had special obligations because of their training to heal, authors have special obligations because of their training to communicate truth effectively.

Just as medical professionals' resistance carried particular weight because of their expertise, authors' resistance to euphemistic language carries authority because of their understanding of how words work.

Contemporary book censorship efforts often target precisely the books that expose uncomfortable truths about how language can be used to dehumanize populations.

Books about slavery, genocide, immigration, and systematic oppression face challenges because they name realities that euphemistic language tries to obscure.

The responsibility extends beyond simply avoiding euphemisms to actively exposing them.

Authors can help readers recognize when "enhanced interrogation" means torture, when "collateral damage" means civilian deaths, when "detention centers" mean concentration camps.

By teaching readers to see through manipulative language, authors serve the same function as the medical professionals who exposed "gentle death" as murder.

Authors also carry the responsibility to humanize populations that dehumanizing language targets.

Just as Aziz chose to document not just the perpetrators of medical crimes but also the heroes who resisted, contemporary authors can choose to tell stories that restore humanity to people whom political language seeks to reduce to categories, problems, or threats.

The power of storytelling to counteract dehumanizing language cannot be overstated.

When authors tell the individual stories behind immigration statistics, the personal experiences behind policy abstractions, the human faces behind bureaucratic categories, they make it much harder for euphemistic language to maintain its psychological distance.

Perhaps most importantly, authors can model the kind of precise, honest language that serves truth rather than propaganda.

By refusing to accept euphemisms, by calling things by their proper names, by insisting on clarity over comfort, authors can help rebuild the linguistic foundation that democracy requires.

Conclusion: The Vigilance Democracy Requires

The progression from "gentle death" to genocide wasn't inevitable—it was enabled by the gradual acceptance of dehumanizing language and the failure of enough people to recognize the danger in time.

The medical professionals who resisted Operation T4 understood that protecting disabled patients required vigilance about language, policies, and the gradual erosion of human dignity.

Their successful resistance offers both warning and hope for contemporary times.

The warning is clear: euphemistic language that dehumanizes any population threatens everyone's safety, because the logic of elimination, once accepted, expands predictably.

The hope is equally clear: sustained, coordinated resistance by ordinary people can expose truth, protect vulnerable populations, and preserve democratic values.

The choice facing contemporary society mirrors the choice that confronted German professionals in the 1930s and early 1940s: accept euphemistic language and gradual dehumanization, or resist through truth-telling, professional integrity, and coordinated action.

The historical precedent shows that resistance can work—but only if enough people recognize the danger and act before it's too late.

Philippe Aziz documented these stories not just to preserve history, but to prepare future generations to recognize and resist similar patterns.

In our own time, when euphemistic language again obscures systematic harm to vulnerable populations, his work serves as both warning and instruction manual.

The forgotten heroes who successfully resisted "gentle death" remind us that ordinary people's extraordinary courage can still triumph over institutional evil—if we're willing to learn from their example and apply their lessons to our own challenges.

The vigilance democracy requires isn't just about voting or political engagement—it's about refusing to accept language that dehumanizes anyone, recognizing when euphemisms mask cruelty, and insisting on truth even when it's uncomfortable.

When we honor the memory of those who resisted Operation T4, we commit ourselves to the same vigilance, the same courage, and the same insistence that all human lives deserve dignity and protection.

This concludes our three-part series exploring Philippe Aziz's documentation of Nazi medical resistance and its lessons for contemporary times. Thank you for joining this difficult but necessary journey through history's warnings and hope.